Cultural and Minority Affairs

This group works toward increasing cultural responsiveness and the thoughtful engagement of minority status individuals in physical therapy through professional and community education, outreach, and advocacy. Looking for someone who is: socially minded, collaborative, resourceful, and committed to serving all underrepresented communities.

|

Katie Farrell, Co-Chair

|

Talina Corvus, Co-Chair

|

Have questions for this committee? Contact Us

July/August 2021

Click on the flyer above to complete the survey. If you are not able to click the link, please copy and paste the following url https://pacificu.co1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_9pMoEzA31qolfqC.

The survey will be open until August 25, 2021.

January 2021 - The most recent Cultural & Minority Affairs (CMA) meeting was on Jan. 18th. The committee is currently working on contributions to the APTA-OR Annual Conference, Cultural Competence continuing education programs that have been approved by the Oregon Health Authority, and planning for a virtual social gathering.

PTs, PTAs and students are always welcome to find more information about CMA on the APTA-OR website and get in touch with our committee if they have questions.

Talina Corvus-Marshall, Chair

CMA Committee COVID Series - Part 3

The Inequities and Challenges Facing Individuals Who Identify as LGBTQ+ during the COVID-19 Pandemic

July 2020 - In a three-part series, the Cultural and Minority Affairs Committee aims to highlight the increasing health disparities in underserved and vulnerable populations during the COVID-19 pandemic. In part one, we focused on immunocompromised/immunosuppressed individuals, followed by ethnic and racial disparities in part two. In this final segment, we direct attention toward the inequities and challenges facing individuals who identify as LGBTQ+ with a focus on the transgender community.

In a recent research brief, titled “The Lives and Livelihoods of Many in the LGBTQ Community are at Risk Amidst COVID-19 Crisis” by the Human Right Campaign Foundation (HRC), the authors point out that the associated risk factors for infection and health complications for LGBTQ+ people are mostly unknown. Currently, the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) has negligible information on the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases of individuals who identify as LGBTQ+. As of July 16, 2020, two individuals (self-identified as non-binary) out of 12,438 total individuals with confirmed COVID-19 cases are known to be LGBTQ+ (OHA, 2020). It is reasonable to assume this proportion is not accurate. According to a Gallup Poll, conducted nationally between 2012-2014, the Portland Metropolitan region had the second highest population of adults who identify as LGBTQ+, (5.4% compared to San Francisco’s 6.2%), and Portland continues to be the second highest as of 2016 (Williams Institute, 2016). One example of systemic pressure is a recent change in “sex discrimination” recently finalized by the Department of Health and Human Services on June 12 of this year, which has likely prompted individuals to omit reporting their sexual identity (OHA reports 36 unknown sexual identities for confirmed COVID-19 cases, as of July 16, 2020). The ruling provides protections for those who identify as either “male or female” when seeking healthcare and health insurance, while excluding similar protections to individuals who identify as LGBTQ+ (Health and Human Services, June 2020).

Why are individuals who identify as transgender more at risk during the pandemic?

The HRC notes that 3 million LGBTQ+ people are recognized as frontline and/or essential workers nationally (e.g., restaurants, food service and hospitals); thereby, increasing their susceptibility to COVID-19 exposure and compounding the health disparities seen within this already marginalized group of individuals. LGBTQ+ adults tend to have a higher rate of smoking every day when compared to non-LGBTQ+ people (37% and 27%, respectively). Secondly, 21% of LGBTQ+ adults have asthma when compared to 14% of non-LGBTQ+ people. Both respiratory risks result in experiencing a greater rate of complications associated with contracting COVID-19. In addition, 1.4 million LGBTQ+ adults are diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, which has been recognized as a considerable risk factor for contracting and increasing the complications associated with COVID-19. Beach et al., concluded that sexual minorities may be at an increased risk for diabetes than their heterosexual peers, while citing that gay and bisexual men were more likely to report a diagnosis of diabetes over a lifetime when compared to heterosexual men (11.4%, 14.2% and 10.8%, respectively). Similar findings were not observed for lesbian and bisexual females when adjusting for age; however, lesbian and bisexual females were at an elevated risk for obesity. Lastly, according to the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy, LGBTQ+ individuals account for 5%-10% of the general population, which the American Cancer Society estimates will be approximately 135,000 newly diagnosed cases of cancer in 2020 within the LGBTQ+ community (>45,000 cancer deaths within LGBTQ+ individuals). Additional information on COVID-19 and how it relates to immunocompromised individuals, can be referenced from part one of our series.

Prior to the COVID-19 era, “The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey” published by the National Center for Transgender Equality reported that within the transgender community:

- 23% were denied or evicted from housing or experienced some form of housing discrimination;

- 30% of the survey respondents reported being fired, denied a promotion, or experienced some form of harassment in the workplace;

- 12% had a household income between $1 and $9,999 per year compared to 4% in the total population of the United States.

With the significant rise in job losses and the subsequent rent crisis from the effects of COVID-19, the aforementioned numbers are likely to worsen. Moreover, after state mandates from COVID-19 were implemented, Wilson and Conron (2020) revealed that the overall percentage of LGBTQ+ people who reported not having enough food to eat was more than twice the proportion found in the general population (Williams Institute, 2020).

Researchers from the University of California, San Francisco School of Nursing and Stanford University, through an ongoing longitudinal study titled the Population Research in Identity and Disparities for Equality (PRIDE) Study, surveyed participants regarding mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic (Flentje et al., 2020). Their results indicate that accounts of anxiety and depression significantly increased in LGBTQ+ individuals who did not report either condition prior to the pandemic (Flentje et al., 2020).

Meyer (2007) proposed a minority stress model describing three underlying causes for health disparities in minority populations:

- Minority stress is a unique stress apart from the types of stress experienced by everyone; minorities must develop additional coping responses to combat the added strain.

- The stress experienced by the LGBTQ+ community and other minority populations is continuous. This perpetual body-stress response and long-term cortisol release can lead to chronic medical and mental health conditions.

- Minority stress is integrated into many systemic structures and processes within society

For example, transgender individuals must overcome multiple systemic barriers to receive gender affirming surgery including access to information, financial burden, and identifying a physician to perform the surgery or surgeries (El-Hadi, Stone, Temple-Oberle, & Harrop, 2018).

The impact of COVID-19 on hospital systems resulted in gender affirming surgeries being delayed or canceled entirely. For those fighting to overcome these systemic hurdles, receiving this information can be devastating. As one transgender individual stated, “Everything I was doing and progressing has been taken…It’s been torture” (Cohen, April 10, 2020). These surgeries, defined as elective to medical facilities and insurance companies, are integral to identity realization and gender congruence, the “degree of harmony we feel in each dimension of our gender” (Gender Spectrum, 2020). The stress of the delay in surgery may further be compounded by events that we all are facing, including job losses or furloughs, along with the financial strain of paying mortgage or rent. Transgender individuals, however, are also burdened with decreased access to hormone therapies, medication, and mental health care from the impacts of social distancing and closures of medical facilities. Other stressors include the ongoing state and national legislative issues that reduce access to health care for the transgender community, such as insurance coverage for telehealth visits or the recent elimination of protections against sex and gender discrimination in medical care. Concerns over higher rates of depression and suicidal ideation in the transgender community are growing (Cohen, 2020).

How can physical therapists help?

Physical therapists should strive to create an inclusive environment in the clinic. An immediate way to make an impact for individuals identifying as transgender is to follow intake interview guidelines outlined by Heck, Flentje, and Cochran (2012). They recommend adopting the language of the patient when providing physical therapy care, such as using “partner” or “co-parent” instead of gender-specific terms like husband/wife or father/mother. The authors emphasize that using patient-preferred terminology is necessary, as diversity in language within the LGBTQ+ community exists and it serves to decrease one of the stressors for this community. Prior to conducting the evaluation, physical therapists should also discuss their clinic’s confidentiality and documentation procedures with the patient to gain an idea of their preference in use of pronouns along with their feelings of safety, especially when treating adolescents or documenting in the presence of the patient. Physical therapists can also ensure that their clinic’s intake paperwork uses gender neutral language, has a “write-in” option for gender, and avoids asking the question of marital status, as LGBTQ+ individuals may be unable to marry due to legislative or societal restrictions. Using the term “relationship-status” or listing options like “partnered” or “long-term relationship” are more inclusive.

Finally, physical therapy providers can examine their own personal biases surrounding the LGBTQ+ community. Just as many of us obtain advanced training for specialization, being a skilled practitioner for the transgender community requires further education, openness to changing current practice, and seeking guidance and mentoring from others that are more knowledgeable in this realm. Preliminary self-examination questions presented by Heck et al. (2012) and modified for the physical therapy profession, include:

- Have I acquired the necessary training and knowledge to be competent to work with LGBTQ+ patients?

- Have I examined my attitudes and beliefs and pre-existing notions about individuals who identify as LGBTQ+?

- Will LGBTQ+ individuals feel comfortable coming to my clinic and will other members of the clinic treat these patients with respect?

- Does my intake and assessment paperwork honor the many dimensions of patient diversity?

- Do I ask my patients affirming and open-ended questions about relationships, family, sexuality, and gender?

For specific patients:

- Am I familiar with the research regarding LGBTQ+ physical and mental health that applies to this particular patient?

- Have I assessed the impact of minority stress and discrimination on the patient, and factored this into my plan of care?

Where can I learn more about providing health care for the LGBTQ+ community?

Organizations like PTProud, of the Section on Health Policy and Administration of the APTA, and the GLMA Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQ Equality have information on best practices for providing care to patients of the LGBTQ+ community. More information on legislative and healthcare issues can be found through the Human Rights Campaign and the National Center for Transgender Equality.

Resources:

References:

- American Cancer Society. (2020). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (LGBTQ) people with cancer fact sheet. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/cancer-control/en/booklets-flyers/lgbtq-people-with-cancer-fact-sheet.pdf

- Beach, L, Elasy, T, and Gonzales, G (2018). Prevalence of Self-Reported Diabetes by Sexual Orientation: Results from the 2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. LGBT Health, 5(2), 121-130

- Cohen, L. (2020, April 10). Coronavirus pandemic highlights barriers to health care for transgender community. CBSNews.com. Retrieved from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/coronavirus-transgender-lgbtq-health-care-in-covid-19-pandemic/

- El-hadi, H., Stone, J., Temple-Oberle, C., & Harrop, A.R. (2018). Gender-affirming surgery for transgender individuals: Perceived satisfaction and barriers to care. Plastic Surgery, 26(4), 263-268.

- Flentje, A., Obedin-Maliver, J., Lubensky, M. E., Dastur, Z., Neilands, T., & Lunn, M. R. (2020). Depression and Anxiety Changes Among Sexual and Gender Minority People Coinciding with Onset of COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of general internal medicine, 1-3.

- Gender Spectrum (2020). The language of gender. Retrieved from https://www.genderspectrum.org/articles/language-of-gender

- Health and Human Services (2020, June 12). HHS Finalizes Rule on Section 1557 Protecting Civil Rights in Healthcare, Restoring the Rule of Law, and Relieving Americans of Billions in Excessive Costs. Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/06/12/hhs-finalizes-rule-section-1557-protecting-civil-rights-healthcare.html

- Heck, N.C., Flentje, A., & Cochran, B.N. (2013). Intake interviewing with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender clients: Starting from a place of affirmation. Journal of Contemporary Pscychotherapy, 43, 23-32.

- James, S.E., Herman, J.L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. (2016). The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality.

- LGBT Demographic Data Interactive. (January 2019). Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law.

- Movement Advancement Project (2020, July 13). LGBT Populations. Retrieved from https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/lgbt_populations

- Newport, F. & Gates, G.J. (2015, March 20). San Francisco metro area ranks highest in LGBT percentage. Gallup.com. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/182051/san-francisco-metro-area-ranks-highest-lgbt-percentage.aspx?utm_source=Social%20Issues&utm_medium=newsfeed&utm_campaign=tiles

- Oregon Health Authority. (2020). Covid-19 Updates. Retrieved from https://public.tableau.com/profile/oregon.health.authority.covid.19#!/vizhome/OregonCOVID-19CaseDemographicsandDiseaseSeverityStatewide/DemographicData?:display_count=y&:toolbar=n&:origin=viz_share_link&:showShareOptions=false

- Reinberg, S. (2020, July 6). Coronavirus ups anxiety, depression in the LGBTQ community. USNews.com. Retrieved from https://www.usnews.com/news/health-news/articles/2020-07-06/coronavirus-ups-anxiety-depression-in-the-lgbtq-community

- Wilson, B.D.M. & Conron, K.J. (2020, April). National estimates of food insecurity: LGBT and Covid-19. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. Retrieved from https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Food-Insecurity-COVID19-Apr-2020.pdf

CMA Committee COVID Series - Part 2

Deciphering Demographics

COVID Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Oregon

June 2020 - The current COVID-19 health crisis is affecting everyone in our society, but it’s clear that it is also having a disproportionately negative impact on the lives and health of racial and ethnic minorities. Viruses have no bias, but based on a host’s socio-ecological factors, they do have an unequal impact. Currently, demographic data put forth by the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) suggests that minorities have the highest prevalence of onset, while non-Hispanic Whites have the lowest incidence (2020). In Oregon, Latinx individuals make up 13% of the population but are 31% of all confirmed COVID-19 cases, the largest disparity in the state. Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders/Native Americans make up 2.3% of the general population and 4% of confirmed cases, while African Americans comprise approximately 2% of the population and 3% of confirmed COVID-19 cases (Census, 2019; Covid Tracking Project, 2020, OHA, 2020).

As virus transmission rates are still fluctuating and are not yet fully understood (Court & Baker, 2020) those who are at the highest risk for exposure remain the most vulnerable. In Oregon, the essential, or frontline, workforce is reported to have proportional racial and ethnic representation, although women are disproportionately frontline workers both locally (63%) and nationally (52%) (Ayesha, 2020; Economic Policy Institute, 2020), yet we still see high rates of infection within minority populations. Oregon Live, however, states that Latinx individuals are overrepresented in the frontline workforce (2020). That discrepancy in reporting may be due to the nearly 74,000 undocumented immigrant workers, who are also ineligible for medical benefits and working in agriculture, childcare, restaurants, and as day laborers (Penderson & Henderson, 2020).

The alarming cases of COVID-19 may be more closely related to where individuals are living, learning, playing, and working. These environments place them at an increased risk of contracting the virus, which emphasizes the importance of taking into consideration an individual’s social-ecological background. According to the COVID-19 in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups report, these individuals live in more densely populated communities, in multi-generational homes, and they are most likely to be essential workers. These factors increase their risk to exposure, both at work and at home, and their likelihood of spreading the virus within their communities. (CDC, 2020)

Socio-ecological status is likely a major contributor to an individual’s access to health equity. However, when discussing health disparities, we often do so as they pertain to only a few categories; usually race, sometimes age or gender. In doing so we gain some information but we also lose some information by drawing lines that lack nuance when grouping individuals and without taking into consideration what effect that may have. Often in healthcare, we speak of individuals as a collective and therefore assume that collectively these individuals may have access or lack thereof to a certain set of resources, broadly. We use demographic data to frame these discussions and there are strengths and weaknesses to this type of data.

Deciphering Demographics

Race in this country has been under constant construction since its foundation.

When health outcomes are reported along racial/ethnic demographic lines, it is important that we understand that while the data provides us with information that is important it also lacks information about deeper disparity and deeper resilience. Race is a social and political construction that is not based on biological science (Rogers & Bowman). “White” first appeared as a racial classification in the 17th century with the function of racializing slavery, distinguishing those who could not be subjected to chattel slavery (“White” individuals) and those who could (“Black” individuals) (Dee, 2003). The categorization of White grouped an ethnically and culturally diverse group of individuals under a homogenizing label. The first census conducted in the United States was performed in 1790 and it accounted for three categories of people; free White males and females, other free people, and “slaves”. Who counted as White, and what diversity was present in any of these categories was not accounted for. While African Americans were given various classifications, no other race was accounted for until 1860 when “American Indian” was added, but only for those individuals living in White society. They were not fully counted until 1890. “Chinese” as a classification was introduced in 1870, and Japanese in 1890. Broader classifications for “Asian” did not appear until 1920. In 1910, the vast majority of people categorized as other were Korean, Filipino, and “Asian Indians” or “Hindus”. Additional categories to account for ethnicity were introduced in 1920; however, Pacific Islanders and Hawaiians were grouped with Asians from 1960-1990. They were recognized independently on the 2000 census for the first time. “Mexicans'' were counted as a race for the first, and only, time in 1930. Latinx communities then disappeared from the census until 1970. The term “Hispanic” was introduced culturally in the 70’s for political reasons (Demby, 2014), and 1970 is also when classifications for “Hispanic Ethnicity” appear on the census and remain. 2020 is also the first year that people of any race could provide additional information about their places or countries of origin. Prior to 2000, Americans could not include themselves in more than one category, so individuals who were born and raised in multiracial or multiethnic families were counted and represented in only one category. As the census continues to move to generating more representative data, 2020 is the first year that people of any race can provide additional information about their places or countries of origin within their racial categories. (Pew Research Center, 2020)

When we report or read demographic information, we are conceptualizing and categorizing people by racial constructs based on skin color, countries of origin, continents of origin, and geographic regions of origin, that were often politically defined by colonizing powers, as though they are equally meaningful. It is, perhaps, no wonder that we do not have a firm understanding of the construct of “race” in this country. It is the census categorizations that set the standard for how we talk about race in healthcare, and beyond, but diversity within the racial and ethnic groups established contain a greater diversity of health considerations and outcomes than our data tends to account for. Due to the social, political, and cultural nature of race, racial categories can have different meanings in different geographic regions (Demby, 2014). Also, with the rising numbers of multiracial individuals, along with people choosing to claim all aspects of their racial and ethnic heritage, “other” or “two or more races” is the fastest growing demographic in the US. There are benefits to being able to group individuals, for the sake of data generalization. While it helps streamline the complexity of having to filter through a magnitude of independent identities and experiences, it is at the expense of assuming that all individuals belonging to one group have the same lived experience.

So, what can the categories we are provided with in health demographics tell us and what remains obscured? The next section will speak to each of the primary racial/ethnic categories used on the census and in health demographics. We would like to make it clear that is not an exhaustive list or account, and there is no way that we could speak to the history and experiences of each racial/ethnic group that is mentioned, and not mentioned, here.

White

Individuals who are represented in this category generally include people who are of Northern, Eastern, Southern European descent, but it is also common for people of North African, Middle Eastern, and Central and South American descent to identify as White, racially, although they may still maintain other ethnic identities. (Example: White Cuban as compared to an Afro- or Black Cuban).

Obscured: White is a much more ethnically, culturally, and economically diverse demographic than we often account for when envisioning health and expectations for this population.

Hispanic, Non-White

According to the U.S. Census for 2020, Hispanic is not a race but instead viewed as an opportunity to identify one’s heritage, nationality, lineage, or country of birth of the person or the person’s parents or ancestors before arriving in the U.S. The categorization defines “Hispanic or Latino” as a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture of origin (e.g., Salvadoran, Dominican, Colombian, Guatemalan, Spaniard, Ecuadorian, etc.), regardless of race. In the 2010 census, 37% of Hispanics—18.5 million people—said they belonged to “some other race.” Among those who answered the race question this way in the 2010 census, 96.8% were Hispanic. And among those Hispanics who did, 44.3% indicated on the form that Mexican, Mexican American or Mexico was their race, 22.7% wrote in Hispanic or Hispano or Hispana, and 10% wrote in Latin American or Latino or Latin (Lopez & Krogstad, 2014) The Census states that race questions generally reflect a social definition of race recognized in this country and not an attempt to define race biologically, anthropologically, or genetically. The U.S. Census notes that people who identify their origin as Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish may be of any race of which there are a minimum of five categorizations. Therefore, no race identification category is available for Hispanic non-whites, aside from identifying as “other” (Census, 2020).

Obscured:In addition to homogenizing a rich diversity of peoples, this single categorization obscures such diversity as Afro-Latinx individuals, who may be “Black and -”, the incredible diversity of culture, language, and race, and the presence of Native Central and South Americans who are not identified but can have different health outcomes due to marginalization, as is seen in Native North Americans (American Bar Association). The aforementioned information is also complicated by those who do not wish to identify individuals secondary to fear of deportation; therefore, U.S. Census figures may not be the most representative data of actual demographics.

Black or African American

Individuals represented in this category tend to be people who are of recent or distant descent from the continent of Africa. This includes the descendants of Africans who were brought to the Americas as free people and those who were subjugated to chattel slavery, immigrants and refugees from African countries or from non-African countries who are also of recent or distant descent of those from an African country.

Obscured: Black or African American is much more ethnically, culturally, and economically diverse than we often account for considering health and health outcomes among populations. People who are recent immigrants or who are raised among different cultural communities can have vastly different health outcomes. That said, the effects of racial inequality, specifically towards African Americans, in this country have been demonstrated to negatively impact health outcomes for people who are perceived to be Black, regardless of their heritage, socioeconomic status, or genetic profile. (Read & Emerson, 2005). For these reasons, making assumptions about health status and risk factors for African Americans, broadly, leaves many people unaccounted for by the healthcare system.

Asian

Individuals represented by this category may have origins in over 20 countries and regions. “The status of Asian Americans has always been ambiguous in a country that sees race as a polarity between black and white” (Kivel, 2017). The U.S. Census identifies Asian as a person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam. This includes people who report detailed Asian responses such as: "Asian Indian," "Chinese," "Filipino," "Korean," "Japanese," "Vietnamese," and "Other Asian" or provide other detailed Asian responses (Census, 2020).

Obscured: “Like every other referent for a racial group, the term Asian American lumps together vastly different cultural groups and subsumes the class, gender and diversity of millions of people” (Kivel, 2017). Also, unlike the multiracial categories of Afro-Latinx or “mixed”, generally assumed to be African American and White, there are no culturally recognized categories for individuals who are both Asian and African American or Asian and Latinx, which leaves them often unrecognized in demographic data.

Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

Individuals in this category tend to represent persons having origins in among any of the original peoples of Hawai’i, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands.

Obscured: Each of these cultures, societies, and nations is distinct, with histories, geographies, and socio-cultural experiences that have shaped their health, migrations, and current community composition in way that are not homogenous.

Native American or Alaska Native

Individuals represented in this category tend to be the descendants of the many and varied nations of the North American continent who were forcibly displaced, killed, and marginalized by European colonists (Look it Up), and now reside in every level and setting of society, from rural and suburban to urban. They may also be of mixed racial and cultural heritage, representing Native and non-Native peoples from various countries and regions.

Obscured: Native American individuals have consistently been undercounted in census and health demographic data. COVID data is no different with information on COVID cases failing to count Native American groups, assigning them to the category of “Other” at times, and is still not completing adequate or accurate counts. (Nagle, 2020). Native Americans are often grouped together as though they are one people when they are composed of many nations, with diverse histories and geographic origins impacting health and health history.

All of that said, the value of obtaining demographic information, in general, is that it allows healthcare providers to see health trends and recognize strengths, disparities, and inequities. It also allows groups of people to report on the status and needs of their distinct communities. This information may grow in importance as the healthcare system strives to meet the needs of a soon to be “majority-minority” U.S. population, as anticipated by 2043 (Economic Policy Institute, 2015), with multi-layered health histories and considerations. As communities continue to evolve, the importance of healthcare providers in recognizing the identities and socio-ecological backgrounds and complexities of their patients, which may influence expected health outcomes, should be critical to the act of providing care. The tendency for practitioners to be content in their familiarity with just one or two racial/ethnic groups positions us to do a disservice to our patients, communities, and profession. As health epidemics and health crisis continue to impact our nation (e.g., Ebola, SARS CoV, COVID-19, obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, etc.), we will need to be skilled at interpreting demographic information with a cultural and historical awareness, through the lenses of social ecology and diversity if we are to work meaningfully towards health equity in our communities.

RESOURCES

REFERENCES

- Ayesha R. (2020) Women make up a majority of essential U.S. coronavirus workers. Axios. Retrieved from https://www.axios.com/women-majority-essential-workers-coronavirus-5a89e6b2-9524-4fe4-b91b-7cd64d769aef.html

- Dee, J. H. (2003). Black Odysseus, White Caesar: When Did" White People" Become" White"?. The Classical Journal, 99(2), 157-167.

- Demby, G. (2014) On the Census, Who Checks Hispanic, Who Checks White, And Why. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2014/06/16/321819185/on-the-census-who-checks-hispanic-who-checks-white-and-why

- Economic Policy Institute. (2020). Who Are Essential Workers? Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/blog/who-are-essential-workers-a-comprehensive-look-at-their-wages-demographics-and-unionization-rates/

- Kivel, P. (2017). Uprooting Racism-: How White People Can Work for Racial Justice. New Society Publishers.

- Lopez, M. H., & Krogstad, J. M. (2014). ‘Mexican,’‘Hispanic,’‘Latin American’Top List of Race Write-Ins on the 2010 Census. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Washington, DC: http://www. pewresearch. org/facttank/2014/04/04/mexican-hispanic-and-latin-american-top-list-of-race-write-inson-the-2010-census.

- Nagle R. (2020). Native Americans being left out of US coronavirus data and labelled as 'other'. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/apr/24/us-native-americans-left-out-coronavirus-data

- Oregon Health Authority. (2020) Covid-19 Updates. Retrieved from https://govstatus.egov.com/OR-OHA-COVID-19

- The Covid Tracking Project. (2020) Racial Data Dashboard. Retrieved from https://covidtracking.com/race/dashboard

- Oregon Live. (2020) Latino enclaves hit punishingly hard by coronavirus in Oregon, new data show. Retrieved from https://www.oregonlive.com/washingtoncounty/2020/04/latinos-enclaves-hit-punishingly-hard-by-coronavirus-in-oregon-new-data-show.html

- Penderson A., Henderson T. (2020). Fields of fear: Oregon farmworkers lack safety net as pandemic threatens jobs, health. Street Roots. Retrieved from https://www.kgw.com/article/news/local/oregon-farmworkers-lack-safety-net-as-pandemic-threatens-jobs-health/283-60c104c4-6e81-452d-adf3-12c75d3efdf2

- Pew Research Center. (2020). What Census Calls Us. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/interactives/what-census-calls-us/

- Read, J. N. G., & Emerson, M. O. (2005). Racial context, black immigration and the US black/white health disparity. Social Forces, 84(1), 181-199.

- Smith M. (2020). Native Americans: A Crisis in Health Equity. American Bar Association, 43(3). Retrieved from https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/the-state-of-healthcare-in-the-united-states/

CMA Committee COVID Series - Part 1

Health Inequities in COVID Times:

Immunocompromised and Immunosuppressed Individuals

May 2020 - As Oregon begins to make moves towards returning to more social work, life, and recreation, it is important that we do so while taking care to protect the more vulnerable individuals among us. The Cultural and Minority Affairs Committee will be discussing this topic over the next few months, as our health, safety, and social status unfolds.

This month, we would like to focus on the portion of the U.S. population that lives with an impaired immune system. It is not known precisely what percentage of the population falls into this category, (turns out we do not keep track) but it has been estimated that roughly 3% (2.7%) of the adult population would be classified as immunosuppressed or immunocompromised (Harpaz et al., 2016). For Oregon, that means approximately 102,000 people, not including children and youth (Census, 2019). While there are numerous primary and secondary reasons for immunocompromise; congenital disorders, medications, cancer and transplant treatment, malnourishment, age related immunosenescence, and more (Schall, 2015), the lived outcome is the same, greater susceptibility to infection. As providers who see our patients face to face, in closed environments, and for extended periods of time, it is critical that we, as professionals and as individuals, follow transmission prevention guidelines to ensure our patients and their families can receive care without increased risk to their health, or ours. In practice, the APTA has published best practice guidelines for the Physical Therapy profession, including; hand and wrist hygiene, containing coughs, sneezes, and yourself, if you feel ill, as well as regular cleaning and disinfecting of all tools and surfaces in your work settings (Levine et al., 2020). Working broadly within the healthcare system, physical therapists also have an opportunity to provide meaningful education to patients and their families about risk factors and prevention strategies to protect the health of those that may be compromised, using resources from the APTA and CDC. In our daily lives, the prevailing advice is that limiting our movements through the community can help limit the movement of the COVID-19 virus, restricting its access to those among us who are at a heightened risk and dependent on the health and immunity of those around them.

- D’Antiga, L. (2020). Coronaviruses and immunosuppressed patients: the facts during the third epidemic. Liver Transplantation.

- Harpaz, R., Dahl, R., & Dooling, K. (2016, December). The prevalence of immunocompromised adults: United States, 2013. In Open Forum Infectious Diseases (Vol. 3, No. suppl_1). Oxford University Press.

- Levine, D., Spratt, H., Hanks, J., Woods, C. (2019) Novel Coronavirus: A Wake-up Call for Best Practices in Preventing Pathogen Transmission. APTA #PT Transformations.

- Schall, T. (2015) How Many Americans are Immunocompromised?. Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics. Retrieved from http://bioethicsbulletin.org/archive/how-many-americans-are-immunocompromised

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2019) Quick Facts Oregon. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/OR

April 2020

The CMA Committee continues to actively plan education sessions to be offered through the OPTA this year, as well as a minority student/practitioner survey project. Recently we chose to postpone our spring conference social event in light of COVID-19 social distancing recommendations, but will continue to look for chances to come together as a community for learning opportunities. It is the committee's goal to collaborate with other OPTA committees to continue supporting OPTA efforts and growth.

-Erin Kettler & Talina Marshall Corvus

July 2019

CMA Committee Update

Follow us on Facebook!

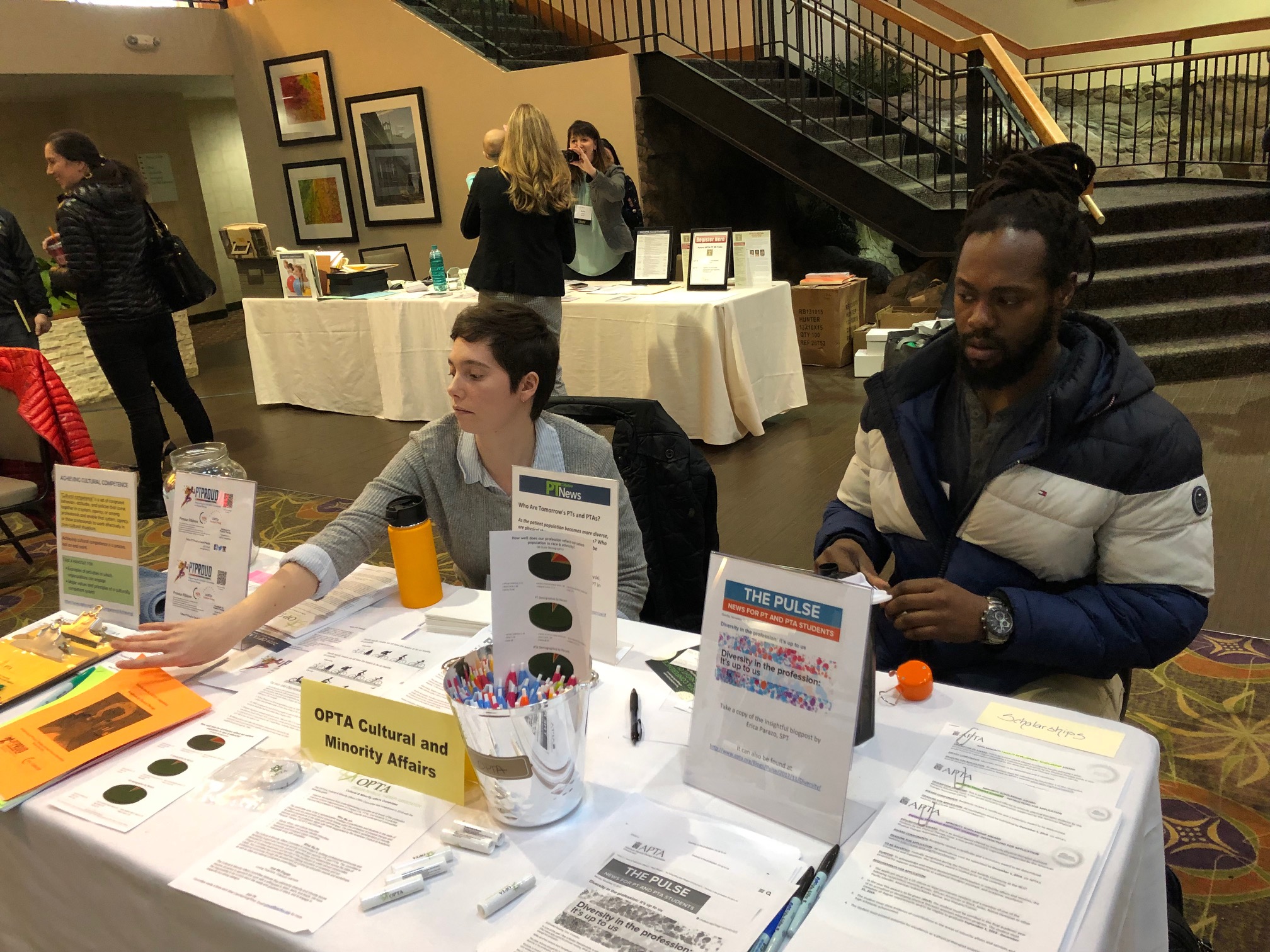

The OPTA Cultural & Minority Affairs (CMA) committee, started in 2018, officially began meeting toward the end of last year and held their first social event at Portland Center Stage on March 8th, 2019, ahead of OPTA’s spring conference.

The committee also hosted a table at the OPTA Spring Conference. Educational materials related to health disparity outcomes affecting communities of color and the LGBTQ+ community were available. We were pleased to see interest and participation in the committee’s work grow from both the social and tabling events.

The OPTA Cultural & Minority Affairs committee is working to find and build community and assess the wants and needs of minority practitioners in Oregon. We are looking for as much input as we can get from current and future PTs/PTAs. Our desire is to focus on needs and opportunities identified by the committee and the community.

To find us on Facebook, search for OPTA Cultural & Minority Affairs Committee. We encourage all members to follow the page here.

OPTA

Cultural & Minority Affairs Committee

The OPTA’s Cultural & Minority Affairs (CMA) Committee was established in 2018 with the following goals:

- Improve involvement from underrepresented minorities at all levels of the profession

- Improve cultural responsiveness of Oregon PTs, PTAs, and students in practice

- Improve the profession’s engagement with minority and underserved communities

Who We Are

The committee aims to be a representative coalition of practitioners and students in the state of Oregon who are passionate about minority issues within the profession of physical therapy and its patient populations at the state and national level. The committee’s consideration of minority statuses within the profession aligns with those established by the American Council of Academic Physical Therapy (ACAPT) and includes:

- Racial, ethnic, and cultural minorities

- Sexual orientation and gender identity minorities

- Nationality and immigrant status minorities

- Individuals living with disabilities

What We Do

The Cultural & Minority Affairs Committee is committed to building professional community and facilitating support and mentorship among current and aspiring PTs and PTAs. The committee is dedicated to creating community outreach opportunities and relationships across the state of Oregon to increase awareness and service of the profession to under-served communities. Lastly, this committee has committed itself the ongoing education of ourselves and our professional community through the development of continuing education events and workshops, as well as state and national conference presentations.

How We Engage

Loving Teachers. Gracious Learners.

The Cultural & Minority Affairs Committee believes that addressing diversity and minority issues requires all parties to approach this work with a willingness to listen, learn, and teach. We have the responsibility to be curious about the needs and positions of others, and to engage in respectful but daring dialogue.

Join Us

Committee meets 4 times each year (Jan/Apr/Aug/Nov). See OPTA Calendar for dates and times.

|